Sunsetting a fintech app, some learnings

This post is part of a series on the learnings acquired on developing a Fintech native app for some years.

About three years ago, on Dec 28, 2019, the first native app for Devengo was published in the App Store. On launch, we were laser-focused on providing the best salary advance solution in Europe, and our native apps were our most critical user touch point. Next week we will remove our apps from the stores, so what happened?

A mountain of hard work and a river of sweat allowed us to put our service in the hands of some of the largest employers in Spain, companies with thousands -sometimes tens of thousands- of employees. Most loved and cherished our service, and although there are always things to improve in digital service, we got compliments on the quality of our product from both customers and users.

However, as time passed, even with this positive customer feedback, it became clear that we were not in a position to win the market. The main reason was that the sales cycle was very long (the biggest customers took up to 6 months from initial contact to production launch), making raising capital a critical ability that, unfortunately, was not part of our primary skillset. That slowness made the feedback loop on product development take too long, too, and we tried things based purely on intuition due to the lack of evidence.

You can read about the pivot in detail here. However, the main takeaway is that as part of those learnings, we finally decided to pivot the company to focus on what had worked well since day one and had become our strongest skill: fintech infrastructure to make instant payments.

The removal of Devengo native apps from their stores is part of this pivot we started last May, and now that we are closing that chapter, it looks like an excellent moment to retrospect on what we learnt during those years. There were many revealing moments but I think the most important learnings fit in these three ideas:

- Automated, tight release pipelines really help

- Walled gardens are really bad for almost everyone

- Bet on programmers not on tech stacks

Let’s talk today about the first one.

Automated, tight release pipelines really help

In order to accelerate the company launch as much as possible, the app’s development started before the creation of the in-house tech team in Devengo. So the first iterations were built by an app outsourcing studio, and well, they were not very good. There were the too common issues with this kind of contractor (no automated testing, regression bugs, dubious coding practices as hardcoding API keys in the code), a typical result of most of these studios’ clients just looking forward to a turnkey solution and an app in stores.

Nevertheless, one of the things that worried us is that there was no CI setup, much less a release pipeline. When looking at software from an economics point of view (time investments, benefit-cost ratio), one of the main things you should try to avoid as soon as possible are manual, repetitive tasks that occur multiple times a day and throughout the lifespan of the project. The most common one for most projects? The test suite and the deploy/release process.

So, once the core backend team was built, we enrolled a few native mobile developers as the first Devengo mobile team and moved the development in-house. One of the first tasks we embarked on was to design a release pipeline. I personally put a week into the definition of the workflow and the first PoC synthesising the learnings in an internal document:

The pipeline included three main components that build on top of each. Each component provided benefits on its own, so even if we planned to integrate all of them, this could be done progressively and still provide value.

- Per environment apps. Each release of the mobile apps should generate a version for each of the available environments. The strategy to define these environments is platform-specific.

- Build processes as code. The building process should be defined in code to ensure it is reproducible, consistent and automatable. One Fastlane flow per platform was defined to implement this requirement.

- CI integration. The build process was to be run automatically in Devengo’s CI/CD servers to ensure we tested and released consistently.

Per environment apps

All the technical infrastructure in Devengo is isolated in 3 different environments: development, staging, and production. They are multiple reasons for this isolation:

- Independent definition of resources and configuration.

- Integration of different services.

- Increased reliability, preventing staging problems from leaking into production.

- Increased security following a zero-sharing policy.

Ultimately, we added an extra environment (store) to separate our production test app from what users would download from the Apple and Google stores (more on that in a future series post).

Build processes as code

Very early in the research process, it was clear that Fastlane was the most mature tool for cross-platform app automation. With Fastlane, we could cover not only the most basic dev-intensive points (code signing, compilations and test suite running) in the pipeline but even the more product-oriented parts (store metadata and screenshots, betas delivery).

So we settled on using it as the foundation for the pipeline both for iOS and Android. Although the build process contained platform-specific steps and actions, we could define them consistently in structure and configuration data and have the same flow in both platforms. The first version looked more or less like this:

┌────────┐ ┌───────────────────────────┐

│ │░░ │ │ - Git repo based

│ │░░ │ Code Signing Management │────▶ - iOS: certificate + profiles

│ │░░ │ │ - Android: Keystores

│ │░░ └───────────────────────────┘

│ │░░ │

│ │░░ │

│ │░░ │

│ │░░ │

│ │░░ ▼

│ │░░ ┌───────────────────────────┐

│ │░░ │ │ - Build num auto increase

│ │░░ │ Pre-Build │────▶ - Icon adjustment/ Badging

│ │░░ │ │ - Changelog generation/integration.

│ │░░ └───────────────────────────┘

│ E │░░ │

│ n │░░ │

│ v │░░ │

│ i │░░ ▼

│ r │░░ ┌───────────────────────────┐

│ o │░░ │ │ - Compile

│ n │░░ │ Build │────▶ - Archive

│ m │░░ │ │ - Code sign

│ e │░░ └───────────────────────────┘ - Version Bump to repo

│ n │░░ │

│ t │░░ │

│ │░░ │

│ │░░ ▼

│ │░░ ┌───────────────────────────┐

│ │░░ │ │

│ │░░ │ Beta │────▶ - Appcenter

│ │░░ │ │ - Testers notification

│ │░░ └───────────────────────────┘

│ │░░ **

│ │░░ **

│ │░░ **

│ │░░ ┌───────────────────────────┐

│ │░░ │ │ - App Store submission

│ │░░ │ Release │────▶ - Google Play submission

│ │░░ │ │

└────────┘░░ └───────────────────────────┘

░░░░░░░░░░

Code Sign Management

For the first stage, Code Sign Management, both platforms followed the strategy described in https://codesigning.guide by keeping our keys in sync with Git. The general idea was that any sign-related files needed would be stored in two private git repos (one per platform), and the Fastlane processes will create, read, update and destroy these files as needed and push any changes to the repo so it was automatically available for every developer on the company.

The sync actions would ask for a password when they were first to run. This password was stored locally for developers or provided as env var in CI. It would not be stored in the code or the repo and would be used to encrypt/decrypt the files, so everything was encrypted at rest, adding an extra layer of security to the already private repo. This approach required the creation of an ad-hoc Apple ID for iOS that was used for any interactions with the Apple Store and the Developer Portal.

This part involved many tries and some heavy swearing while fiddling with the many little details of digitally signing the apps, especially in iOS, as anyone who has ever gotten to fight with certificate management in XCode can imagine. However, we ended up with a great experience where one could set up a new laptop to release an app in just a few minutes.

Prebuild Operations

Before we could build the apps, there were a few operations we needed to address:

- Automatic version numbering. Each new master commit will generate a new app version for each beta release, ensuring we always had a simple way to check what code we were testing.

- Icon badging: Since we were going to test apps for multiple environments, it would be nice to let the pipeline stamp the icon with a small marker so we could see which one we are using.

![]()

Build

The compilation of the apps was straightforward, but the most platform-specific of the pipeline, as Android and iOS have their own particular compilation stacks. For Android, we kicked off the compilation process via gradle. In iOS, gym took care of all the subtleties of invoking xcodebuild.

Beta

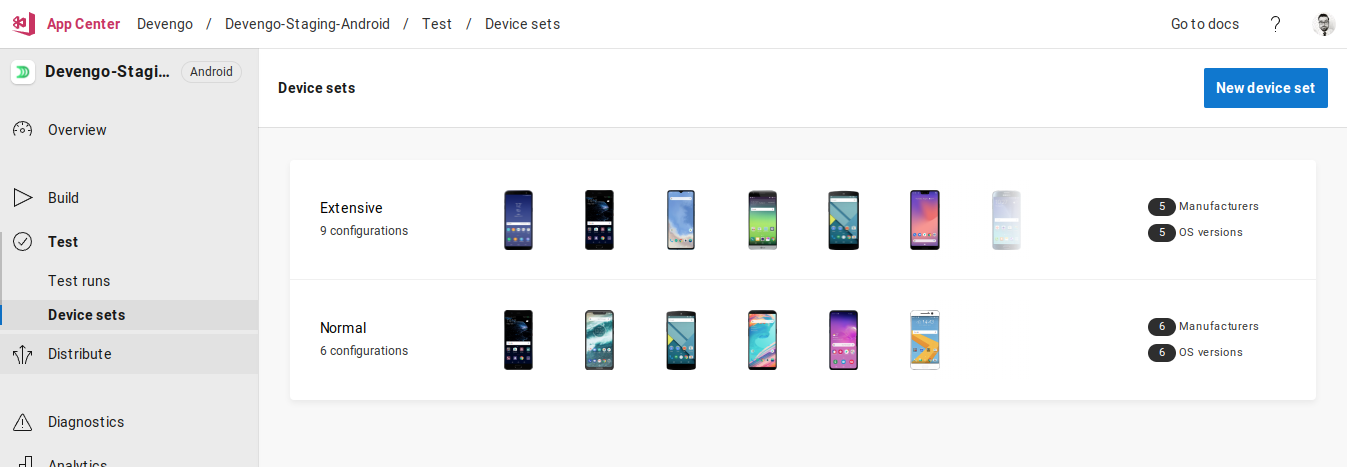

Finally, we distributed iOS and Android apps to testers using a unified platform: Microsoft’s Appcenter. Although both platforms have their distribution channels for betas, we chose a cross-platform solution that will give us just one infrastructure to manage.

Additionally, for Android we were able to build a mobile test lab to run our instrumentation tests on a diverse collection of virtual devices, catching visual bugs before they got to our customers:

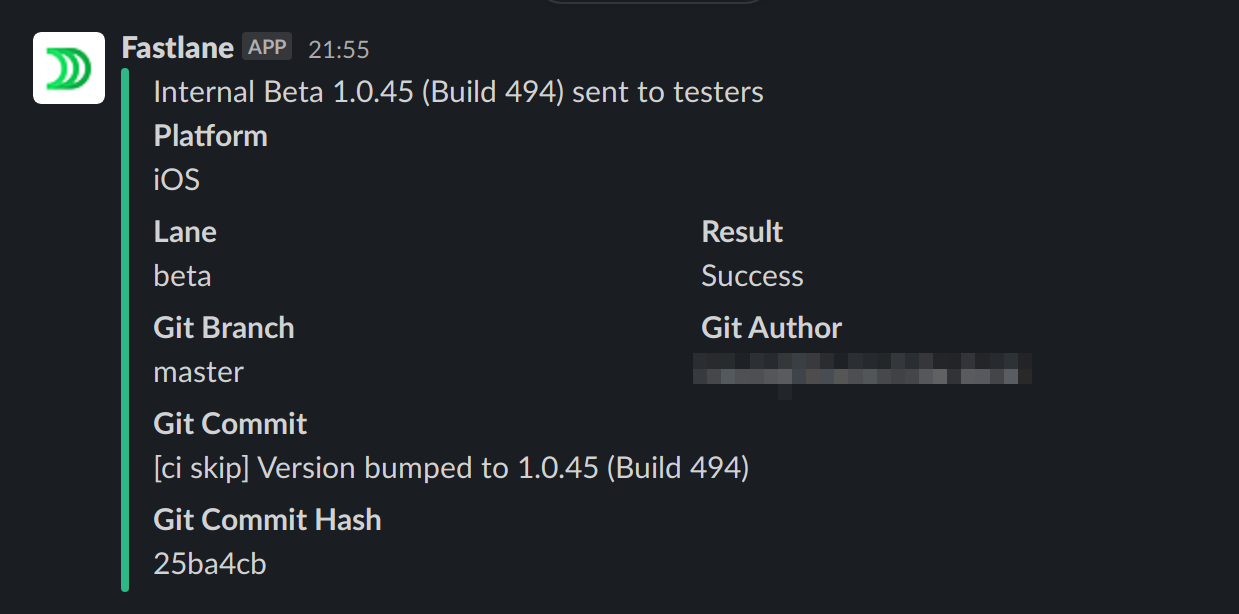

Appcenter took care of notifying and provision the betas to the tester and the pipeline will internally alert the teams about the new beta:

Release

The release process involved the steps taken to build a regular beta but pushing it to the corresponding store instead of Appcenter. The particularities of app submission vary greatly between Google and Apple, but thankfully, Fastlane already provided specific tools for it: supply and deliver.

This part of our pipeline involved the product team more heavily than the rest, as we could automatically submit new metadata for the apps. That involved example screenshots and metadata (descriptions, privacy policies, keywords) in multiple languages, so we hooked that step with our i18n system so it would automatically fetch the last version of all those assets and update it in each store accordingly.

CI Integration

Thanks to the abstraction provided by Fastlane, the integration with our CI services were almost identical for both platforms:

iOS

jobs:

include:

- stage: "Unit Test suite"

name: Run Unit Tests

script: bundle exec fastlane test

- stage: "🚀 Beta delivery"

name: Deliver betas to the team

if: branch == master && type != "pull_request"

script: bundle exec fastlane beta

Android

jobs:

include:

- stage: "Unit Test suite"

name: Run Android Unit Tests

script: bundle exec fastlane unit_tests

- stage: "Instrumentation Test suite"

name: Run Android Instrumentation Tests

script: bundle exec fastlane instrumentation_tests

- stage: "🚀 Beta delivery"

name: Deliver betas to the team

if: branch == master && type != "pull_request"

script: bundle exec fastlane beta

As with our web apps and main core API, this relentless cycle of testing and delivery became the new normal thanks to the app release pipeline. At some point, even some of our backend developers could fix typos and tiny bugs without even having to install any mobile-related stuff. It just worked.

The final system

In the end, we got a 100% automated pipeline that would:

- Test the app for each newly created PR.

- Create a new env-specific version of the app every time a PR got merged in

master. - Deliver the beta automatically to all the testers.

- Alert in slack about the new beta availability.

- Submit the app and an updated version of its metadata in multiple languages to the corresponding store automatically.

The product team would get a new beta ready for testing in staging as soon as the new features were implemented, and we could get from bug detection to release submission in about 30-60 mins (just the time it took to compile the apps).

This system worked for almost three years with very few changes (primarily updates of Fastlane and its plugins), generating hundreds of betas and saving us hundreds of hours of developer time.

However, more importantly, it provided two things:

- It removed the question of how we should ship a beta or a new release. As new developers joined or left the team, not once we had to do special handovers connected with the know-how to publish a beta or release. The system just worked from new laptop configuration to the app being submitted to the store, achieving one of the initial goals of removing any knowledge silo about the release process.

- It established the practice of consistent testing and processes while letting developers focus on the product and forgetting about the underlying testing and releasing infrastructure.

So yes, this is one of the main advices I would give to anyone dealing with security-first, cross-platform native apps: design a solid release pipeline. It will not only save a ton of developer time and tight up the beta testing process but more importantly it will help to establish good testing and deliverability practices in the process.

In the next post I’ll talk about how the closed nature and opacity of the app stores creates negative collaterals for almost everyone involved.

Talk to you soon!